Probably everyone has at one time or another been embarrassed by incompetent allies. In the debates over religion, Christians have too often suffered well-meaning but ultimately uninformed apologetic efforts. However, as atheism has increasingly left the confines of the cultured elite, it too has increasingly been vulgarized and adulterated.

Jerry Coyne is emblematic of this trend. Those who appreciate the august tradition of atheism, which once counted Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Camus, and Gilles Deleuze as members, are understandably hesitant to include under the same banner Jerry Coyne's the intellectually destitute writings. Even among the recent noisome crop of neo-atheists, Jerry Coyne stands out.

With Coyne, one sees the shallowest form of unbelief: his is an atheism without profundity, made up of second hand slogans rather than sustained reflection. He not only misunderstands theism; his understanding of atheism is without subtlety or accuracy. His arguments, such as they are, depend on premises that are both conceptually incoherent and historically ludicrous.

Consider Coyne's recent article, "

The 'Best Arguments for God's Existence' Are Actually Terrible," which appeared in the New Republic. The article takes the form of a refutation of the arguments in David Bentley Hart's new book, The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, and Bliss. Coyne admits that he has not actually read the book, but nevertheless concludes its arguments are false. He claims that Hart's conception of God is "immune to refutation," and therefore that "Hart's argument fails ...." This I designate the "coynian method": the rejection of an argument without first reading it, but with the promise to read it in the future.

(I should say, at this point, that I am not an adherent to the coynian method, and I have read his article prior to critiquing it. One can, however, see Coyne's point: his own argument is certainly stronger if left entirely to the imagination, and most who have read it would prefer, in retrospect, to have put off reading it indefinitely.)

What seems to annoy Coyne the most is the notion that if one is to reject theism, one should deal with the best arguments in its favor. This is an application of the principle that to disprove a position, one must deal with the strongest arguments in its favor.

Sophisticated theologians, according to Coyne, have produced a series of arguments for God's existence: first the argument from design, then the ontological argument, and now the notion of God as the "ground of being." When one argument is disproven, theologians retreat to the next. Hart's understanding of God as the absolute source of being is the current safe preserve for believers and, Coyne things a recently invented academic sophistry.

Anyone remotely familiar with the history of ideas will recognize Coyne's almost total ignorance of both the history and content of theistic arguments. The argument from design is hardly the earliest argument for belief in God. In fact, Paleyesque arguments are quite modern, relying as they do on modern mechanistic notions of nature. The idea of God as the source and end of being, on the other hand, stretches back to the very origins of rational thought: Plato, to cite the most obvious example. Coyne is so ignorant of the history of rational reflection that he manages to get it logically and chronologically backwards.

Coyne does not conceal his nescience behind a screen of vagaries. This much can be said in his favor: Coyne gets things wrong with great specificity. For example, Coyne claims that the idea of "God [as] the condition of possibility of anything existing at all" is not held by "Aquinas, Luther, [or] Augustine." (Nor does Coyne thinks he can explain this idea to his friends. This, at least, is beyond dispute.)

How could Coyne have arrived at this conclusion? Had Coyne actually read any of the three (in any of the arduous years he dubiously claims to have devoted to the subject of theology), he would have discovered that all three considered God to be the transcendent ground of finite being. The coynian methodology (refute first, (maybe) read later) has led Coyne to obviously false conclusions once again.

The virtue of Coyne's forthrightness is that it can be falsified easily. Augustine maintained that God is being itself,1 "the absolute fullness of being and thus the sole primeval source of all being ...."2 Luther's notion of God's otherness strongly distinguished divine from finite existence.3 As for Aquinas, one of the most famous aspects of his theology is his notion of God as "ipsum esse subsistens" (subsistent being itself), which, as Thomas Guarano puts it, means that "God is beyond being, for God is always supra ens, beyond common being."4

Coyne could not have been more precisely wrong. The notion of God as the source of being is not a modern phenomenon, but the traditional theistic notion of God. As Robert Barron quite accurately summarizes it:

"Our greatest theologians, from Origen, through Augustine and Aquinas, to Rahner and Tillich in this century, have maintained that God is not a being, even the supreme being, but rather Being Itself."5

Coyne also poses a series of questions to traditional theism. "[O]n what ground should we believe it?" And "[w]hy on earth does [it] have any force at all?" And again, "what would convince you the God you describe doesn't exist."

A reflective person would have attempted to answer these questions for herself by reading the argument in question and doing her homework on the basics of the subject. But the coynian methodology will not be enslaved by the chains of scholarly rigor.

Had Coyne read Hart, or any decent statement of theism, he would have discovered that God refers to the "one infinite source of all that is: eternal, omniscient, omnipotent, omnipresent, uncreated, uncaused, perfectly transcendent of all things and for that very reason immanent to all things.... He is not a 'being,' at least not in the way that a tree, a shoemaker, or a god is a being; he is not one more object in the inventory of things that are, or any sort of discrete object at all. Rather, all things that exist receive their being continuously from him, who is the infinite wellspring of all that is in whom (to use the language of the Christian Scriptures) all things live and move and have their being."6

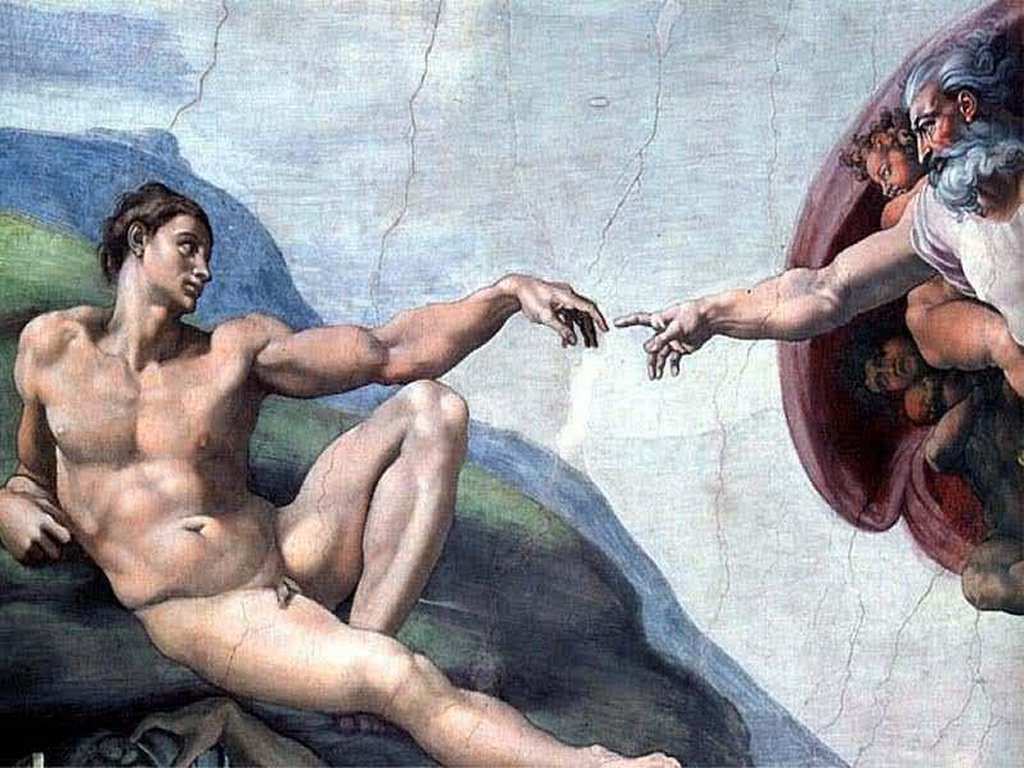

I have no doubt Coyne finds this unintelligible. This, however, has more to do with the limits of his intellect and education than with lucidity of the formulation itself. To completely understand such a formulation requires a fairly solid liberal arts education--it would be useful to have read Plato and Aristotle, as well as have grasped the various doctrines of ontological difference. But the basic idea is by no means limited to an intellectual elite: confusing God with a particular being is idolatry--thus the traditional Jewish and Islamic opprobrium against images. As one finds in Job: "Can you find out the deep things of God? Can you find out the limit of the Almighty?"7

The only actual argument Coyne can muster is that the traditional notion of God cannot be tested. (Or, perhaps more precisely, Coyne expects that were he to study the classical arguments for God, he would it untestable. The Coynian method is pure fideism.) For, Coyne says, if a claim cannot be tested, there is no reason to believe in it.

Coyne's position here is a hash of the Vienna Circle's verifability principle.8 This view has been obsolete for half a century now, for at least two reasons.

First, and most obviously, the testability principle is not itself testable. It is self-contradictory. Second, and more fundamentally, the notion of testability is polyvalent. As Carl Hempel pointed out:

"[T]he criterion is either too strict, in that it rules out sentences which are part of science ('All quasars are radioactive' cannot be conclusively verified and 'Some quasars are not radioactive' cannot be conclusively falsified), or too liberal, in that it allows metaphysical sentences like 'Only the Absolute is perfect.')9

Different claims must be demonstrated by different means, according to the formal and material object of inquiry. The claim that life exists on Mars requires a different type of testing than the claim that all even numbers, when added to other even numbers, results in an even number. To even claim that mathematical or analytical theses are testable is to leave the bounds of empirical science and to expand the term "testable" so thin that it means little more than what one can provide an argument for. Testability and verifiability are equivocal terms. It is Coyne's claim that beliefs should be testable, and not the theistic concept of God, that lacks meaning.

But am I not guilty, like Coyne, of attacking the weakest opponents? If I am to refute atheism, had I not better criticize the intellectually competent rather than pick the low hanging fruit? To be clear, I do not believe atheism to be discredited because its worst arguments are false; nor do I mean to imply that the quality of its tradition should be judged on the basis of its most ignorant opponents. Jerry Coyne should not discredit the whole atheist enterprise. Just as Christian theism is not discredited by Pat Robertson, so atheism is not discredited by Jerry Coyne.

______________________________________________

1 See, e.g., The City of God, XII, 2

2 St. Augustine, De Gen. Ad lit., V, 16 34

3 See B. A. Gerrish, "To the Unknown God": Luther and Calvin on the Hiddenness of God," The Journal of Religion, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Jul., 1973), pp. 263-292.

4 Guarino, Thomas G. Foundations of Systematic Theology. Continuum, 2005. P 250.

5 Barron, Robert E. Bridging the Great Divide: Musings of a Post-Liberal, Post-Conservative, Evangelical Catholic. Rowman & Littlefield, 2004.

6 David Bentley Hart, The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, and Bliss 30.

7 Job 11:7.

8 The question for them was not whether statements were worthy of belief, but whether they were meaningful. See Glock, Hans-Johann. What Is Analytic Philosophy? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 38-9. Though verificationism was no doubt wrong, it had much more subtlety than Coyne's own version.

9 Glock, Hans-Johann. What Is Analytic Philosophy? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 39.